Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen was long considered an un-filmable work. It pushed the formal grammar of comics to new levels, and remains among the top superhero deconstruction narratives. This review will fully discuss the comic and film versions without pause for spoilers.

So when I heard that a film version was coming, I was suspicious. The promo shots and trailers and interviews painted a pretty picture, but the big questions remained:

Would Watchmen be able to translate to the film medium and retain its efficacy? Could it do for superhero films what it did for comics, and for the supers genre? What would have to change for it to do so?

The film version of Watchmen opens with the Comedian’s murder juxtaposed with Nat King Cole’s “Unforgettable.” The visual style is striking, more polished and shiny than Gibbons’ Watchmen, which was studied and deliberate in its messiness. The use of music throughout grounds the story within its historical context.

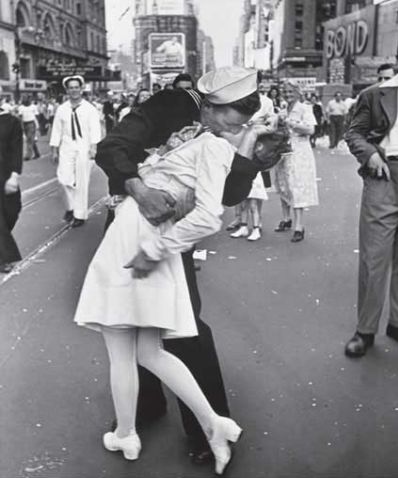

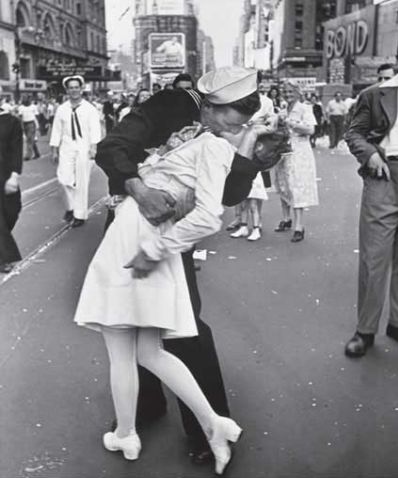

One of the most inspired innovations of film version of Watchmen is the opening credits sequence. The film shows several living photographs over the cource of the alternative history. We go from Nite Owl knocking out a crook in front of a theatre (which i09.com pinned as being a Batman easter-egg) to Silhouette kissing a nurse in a re-work of the iconic ‘soldier coming home kissing nurse’ picture:

The film takes cues from Moore and Gibbon’s intensely dense intertextual text with this and other allusions. It shows Sally Jupiter’s retirement party as a re-figuring of the Last Supper:

It also posits the Comedian as one of the gunmen in the Kennedy assassination, and so on. And the thing tying it all together is Dylan’s “The Times Are A-Changin'”. By the end of the sequence, you know what’s different in the world, you know what the stakes are for the film.

For the most part, Zach Synder’s film of Watchmen follows the graphic novel closely. The Black Freighter text-within-a-text is omitted, to be released separately as a DVD. The basic story beats are there, with more of an emphasis put on the energy crisis aspects of the cold war, such that Ozymandias and Dr. Manhatten’s efforts to fight the dwindling Doomsday Clock by creating a revolutionary energy source.

Synder’s Watchmen turns up the graphic detail of violence, drawing attention to the hyper-violence of the genre in addition to the hyper-sexuality of the fetishistic costumes and their role in the sexual lives of the heroes.

The Moore Continuum

In my earlier post about the Moore Continuum, I talked about how Moore’s critique of superheroes established two ultimate fates of the superhero: A superhero ultimately becomes a Fascist or a Psychopath. Dr. Manhatten represents the superhero being used as a totalitarian tool or weapon of mass destruction, ending the Vietnam conflict in a week of action. The Comedian presents the superhero as a sociopathic rapist turned tool of the establishment (as opposed to the outlaw hero.

Superheroes have been more commonly establishment heroes or outlaw heroes depending on the character or the times. Superman is more usually an establishment hero, Batman and Spiderman more frequently an outlaw hero). Within the history of Watchmen, heroes began as outlaws, were accepted and embraced by the establishment for their work in WWII, used by the establishment in Vietnam, then outlawed by the Keene Act.

Watchwomen

Among the other notable changes is the fact that the female figures in the film have had their smoking habits removed, despite the chain-smoking of the comic. This while Comedian is still allowed his cigars — this ties into the new default cultural assumption now that associates smoking with moral fault. Comedian is an antagonistic/villanous character, so he gets to smoke. But the Jupiter women are figured as victim and heroine, so they aren’t directly associated with that behavior.

In general, Laurie is allowed to be more heroic and agent than in the comic, participating in most of the current-timeline fight scenes and pulling her own weight alongside Nite Owl II. However, the entire narrative of Watchmen remains a critique of the gross excesses of the figure of the superhero.

Feet of Clay

We’ve examined the ‘villains’ of the piece, but what about our protagonists?

Dan Dreiberg/Nite Owl II — an overweight middle-aged shut-in trust-fund kid who wanted to join in the fun, and is impotent without the fetish of his costume and ther aphrodesiac of crime-fighting. Dan is a self-insert character for any and every superhero fan, any kid who grew up loving superheroes so much that their motives are comprimised — is Dan in it because he wants to do good, of because he wants to matter, to be strong, be powerful, be desirable?

Laurie Jupiter/Silk Spectre II — A woman who is defined entirely by her relationships to other characters. She goes into heroing to follow after her mother, falls in with Dr. Manhatten and becomes his sole link to humanity, then imprints on Dan when Dr. Manhatten slips away from her, re-creating her hero worship while acting as a hero herself because she doesn’t know anything else.

Walter Kovacs/Rorschach — A dangerous sociopath raised in a broken home and consdered worthless growing up, he found refuge in crime-fighting, found a way to channel his rage into righteous fury into (somewhat) socially-acceptable channels. For all that he is a crime fighter, he is also a racist misogynist bigot who mooches off of his fellow heroes and unquestioningly murders criminals. His fetish is the Rorschach mask, which he calls his ‘face’ — Kovacs has abdicated his identity and given himself over to his superhero identity, to escape his painful past.

Our ‘heroes’ are far from the paragons of virtue that characters like Superman or Spiderman are made out to be. Now any given hero has their weaknesses — it makes for more human, compelling figures for a hero to transcend their faults to do the right thing. But the weakness and faults in Watchmen’s heroes run so deep that every step of the way, their actions are suspect, must be judged in context with each character’s less-than-heroic motivations — Dreiburg for virility, Jupiter for validation, Kovacs for control. The film does a fine job of following suit with Moore and Gibbons’ storytelling in this regard, such that by the end of the narrative, the protagonists are less reprehensible than the villains, but are hardly role models.

The Ending

In the comic version of Watchmen, Ozymandias created an alien invasion scare by teleporting a giant alien corpse into Times Square, creating a rallying point for humanity to unite against an external threat. The alien is seeded throughout the series, gestured at and shown in parts.

In the film, Ozymandias instead uses the energy sources he and Dr. Manhatten had been making, and replicates effects associated with Dr. Manhatten. He plays on established fears of the godlike figure and re-works nuclear apocalyptic anxiety to provide the unifying threat that ends the Cold War.

In both cases, Rorschach’s journal makes its way to the New Frontiersman, which would raise enough questions about Ozymandias’ involvement to bring down the whole house of cards. In the comic, the New Frontiersman is established throughout the series, but in the film, it is included at the very end without introduction. Regardless, the point is that after Dan and Laurie agree to lie to preserve the costly peace, the truth will come out anyways.

Conlusion

I doubt that Watchmen will revolutionize superhero film the way that it changed superhero comics. It presented an impressive visual style, but satisfied itself by re-creating and somewhat re-working the story. The credits sequence alternative history was powerful, but even with the evocative usage of music (even though Battlestar Galactica fans will forever associate “All Along The Watchtower” with Cylons).

The film’s first weekend performance ($55 million) was, when we take the recession in context, is impressive. Depending on second-week dropoff and general reception, will determine how the film will be remembered in terms of the superhero film trend. We may see other film adaptations of famous comics, though for many of the leading franchises, the adaptation process complicates the possibility of direct adaptations. Marvel Studios continue building towards their massive crossover Avengers film, following the unexpected success of Iron Man and their competition’s success with The Dark Knight. Superhero films don’t seem to be going anywhere yet, and the film was not adapted in such as to condemn or indict other superhero films or their franchises.

If you’ve read Watchmen, seeing the film will let you see iconic moments brought to life, though the adaptation is not perfect, and the changes made have provoked negative reactions from fans, but other fans have been satisfied with the adpatation and noted the increased role given to Silk Spectre II. If you haven’t read the comic but are interested in the supers genre, it’s worth a look to see a critique of the genre brought to the big screen. But then go read the comic afterwords.