Seeing the articles about crunch and worker exploitation in video games makes me think about over-work in the books world.

Things like close-open shifts at bookstores, where booksellers got less than 10 hours off the clock between closing one night and opening the next day. Co-workers at the B&N I worked at faced it more than once or twice.

It’s commonly known in the industry that most editors have to do most of their reading and/or editing at home, *after* putting in full-time hours in the office doing project management/meetings/etc. On salary, so no OT. That’s a culture of habitual crunch.

Publicists given 12 or more titles per month to cover, requiring either shoddy support for some titles and/or substantial, *habitual* overtime. Again, likely uncompensated.

Sales reps asked to read up on the titles they’re selling, which almost always happens outside of office hours. Again, uncompensated. I’m told this happens with some indie booksellers, too.

There was, for a brief time, a pending change to overtime rules and pay in the USA. The Trump Administration has been trying to stop it: overtime-flsa.com/overtime-fairp…

New York State has done a version of this just on the NY level, which is a step in the right direction. Assuming it is enforced and workers aren’t intimidated into working unpaid overtime and not reporting it. I don’t know how it’s working in practice.

Also, let’s talk about how many agents are paid *only* on a commission basis – where it frequently takes several years to build up a client base with sales at a level necessary to make up a living wage.

Oh, yeah, what about the people that write the dang books?

So that’s a lot. And that’s not even including authors. If there’s one type of actor in the publishing industry without whom it could not even begin to function, it’s authors.

How many hundreds of hours of labor goes into each book? What % of book deals actually cover that spread at a level that comes out to even minimum wage? The fastest I ever wrote a novel was 31 days. 71k words for the first draft. About 3 hours a day.

I took Sundays off. So that’s 26 days times three hours a day. I put in *at least* 50 hours of editing & extra writing, and that’s lowballing. But we also have to count outlining, brainstorming, copy editing, page proofs, and promotion. Say another 100 hours for all of that.

(26 x 3) + 50 + 100 = 228 hours. I’d wager that is far onto the low end for a full-length adult novel. Even written very quickly, my $4k advance divides to become $17.5 an hour. Also, it’s not W2 money, that’s 1099 money, so I paid more taxes on it. Plus 15% of the gross went to my agent (which I do not begrudge at all). So I maybe, maybe, hit $15 an hour on that one, pre-tax. So $10 an hour post-taxes.

And that was the *only* novel I’ve been able to write anywhere near that fast. Most I’d say took twice to three times as long. The fast novel was the fourth in a series, so I really knew the characters and had a big arc ending to push for. I was also in good health at the time.

If it takes 500-1000 hours to write a novel and you’re getting $5k to $10 in advances, many of which don’t earn out, you’re looking at maybe $10 an hour, minus agent commission and taxes. For the person *who wrote the damn book everyone else gets paid to help publish*.

Staff and booksellers and other publishing professionals work on a lot of books at once, so the jobs are not a direct comparison. And they for sure add value and deserve to be compensated. Ultimately, my point is that just about everyone is getting screwed until you get into (probably) upper management or the C-suite.

Authors, editors, publicists, sales staff, booksellers, all grist for the mill. And who profits? Who is doing *really well* in this equation? Executives, stockholders, and a *very* tiny percentage of authors. Most of the costs and risks are born by the folks at the bottom. The authors that get dropped when a series doesn’t take off. The publicist let go because they struck out despite working their ass off. The booksellers let go when a chain liquidates to pay out stockholders.

As I think about this, I try to remember that I’m not the only person in the hot seat. I’m in the grind with my agent and (probably) my editors, publicists, sales team, etc. But Passion. But Love of Books. But Literature.

The people at the top are counting on passion. They’re counting on the fact that there is no end to the # of people that want your job or your spot on the list. But we have to do better. We have to demand better.

We can create a world where work is fairly compensated. Where people aren’t pushed to their breaking points to stay on top of the schedule. Where the expectation of unpaid internships doesn’t keep excluding marginalized writers & staffers.

So, what’s the takeaway?

What can I do? What can any of us do?

1) If you’re in a position to set work culture in your office, be a leader in taking care of your staff. In pushing upper management for overtime pay and/or more sensible hours.

2) Remember that you are not alone, not if you’re an author, agent, junior publicist or bookseller. That passion that gets used against us also links us with other people in the field. We can fight for one another.

3) Vote for candidates that support living wages and stronger protections for workers.

4) Investigate unionization and labor advocacy in your workplace.

5) Take care of yourself. Especially if no one else is. And then, if you can, try to help someone else.

In closing, I want to shout out folks that have been banging this drum already, folks like @MattFnWallace, publishing podcasts like @printrunpodcast and @ShipAndHandling, and the games outlet that got me on this track, @waypoint. Follow & support them as you can.

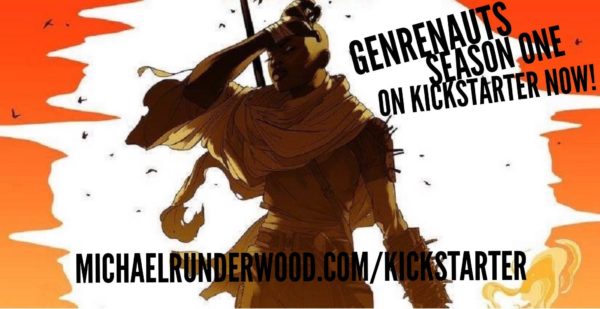

And, if you want, check out my books, like Genrenauts Season One.

Last weekend, I had the fortune of attending the 50th Annual Nebula Awards Conference. I originally wasn’t planning on attending, due to an already-full con schedule, but a friend pitched me on the con, with an intent of having me participate in programming. And the panels being discussed were amazing.

Last weekend, I had the fortune of attending the 50th Annual Nebula Awards Conference. I originally wasn’t planning on attending, due to an already-full con schedule, but a friend pitched me on the con, with an intent of having me participate in programming. And the panels being discussed were amazing.